Flaming red hair, Metallica, pet rescue and a cardboard medal for peeling potatoes – this is the story of a female police officer living in Vytegra, a port town in the Russian north.

Midday. The August sun is at its zenith. A large iron door that leads to the local police station opens up with a scraping noise, and a red-headed woman in a dark-blue uniform steps outside. She sets off to a local supermarket, walking boldly along the narrow pavement covered with deep crinkled cracks – so fast that I barely keep up with her.

"So, you did steal the gin, didn't you?"

"I guess I did," a pinkish middle-aged man with a smell of alcohol on his breath shrugs and suddenly raises his eyes with a ray of hope. "Got a smoke, officer?"

The woman sighs and hands him a thin mint cigarette. Then she briskly nods at her colleagues, meaning it is time to take the troublemaker to the police department.

Twenty minutes later, the penitent thief in a red baseball cap, who introduced himself as Yura, is sitting on a plastic chair at her office, constantly fidgeting and guiltily staring at the floor. He babbles that he ended up in Vytegra by accident – missed his bus and lost his documents – and asks pitifully to call his mom so that she could send him money for another bus ticket to Petrozavodsk. The red-head woman sighs again and gives him her service phone. However, once he starts yelling, she purses her lips in disapproval, takes the phone back and in a strict teacher's voice tells the thief's mom about the accident herself. Then she gives Yura an appraising eye.

"Just what I need here. The bus leaves tomorrow morning. Let's go buy you a ticket 'cause I don't wanna see you in this town ever again, got it?"

With these words, Elena leaves the office. Yura and I spring up and rush after her.

Despite the issued fine, Yura's mood has lightened. My photo camera does not seem to bother him at all – he walks vigorously along the tortuous path, squints in the sun and showers Elena with compliments. She just chuckles and rolls her eyes. She does not know yet that in a few days Yura will be brought to the police department again – wearing the same tracksuit, with a similar guilty look on his face and again, with a harsh smell of alcohol. Elena meets such pilferers at local supermarkets every single day: this is the fate of a probation officer in a small town where the main tourist attractions are a modest river harbor, a cathedral bereft of domes and an old submarine.

Yura finally leaves, and we keep walking fast along the narrow streets.

"So, you did steal the gin, didn't you?"

"I guess I did," a pinkish middle-aged man with a smell of alcohol on his breath shrugs and suddenly raises his eyes with a ray of hope. "Got a smoke, officer?"

The woman sighs and hands him a thin mint cigarette. Then she briskly nods at her colleagues, meaning it is time to take the troublemaker to the police department.

Twenty minutes later, the penitent thief in a red baseball cap, who introduced himself as Yura, is sitting on a plastic chair at her office, constantly fidgeting and guiltily staring at the floor. He babbles that he ended up in Vytegra by accident – missed his bus and lost his documents – and asks pitifully to call his mom so that she could send him money for another bus ticket to Petrozavodsk. The red-head woman sighs again and gives him her service phone. However, once he starts yelling, she purses her lips in disapproval, takes the phone back and in a strict teacher's voice tells the thief's mom about the accident herself. Then she gives Yura an appraising eye.

"Just what I need here. The bus leaves tomorrow morning. Let's go buy you a ticket 'cause I don't wanna see you in this town ever again, got it?"

With these words, Elena leaves the office. Yura and I spring up and rush after her.

Despite the issued fine, Yura's mood has lightened. My photo camera does not seem to bother him at all – he walks vigorously along the tortuous path, squints in the sun and showers Elena with compliments. She just chuckles and rolls her eyes. She does not know yet that in a few days Yura will be brought to the police department again – wearing the same tracksuit, with a similar guilty look on his face and again, with a harsh smell of alcohol. Elena meets such pilferers at local supermarkets every single day: this is the fate of a probation officer in a small town where the main tourist attractions are a modest river harbor, a cathedral bereft of domes and an old submarine.

Yura finally leaves, and we keep walking fast along the narrow streets.

Day 1. "Out of Sight Out of Vytegra" and the Evil Apartment

"You know, I love my job so much that a rare criminal makes me mad. I don't snub them, nothing like that… They are also people. Even though not the best ones," Elena explains on the go, humming some random tune.

Again and again, she greets passersby, coos with babies in buggies, nods at pedestrians – right until we stop by a long wooden house with broken windows covered with dust and dirt. Her voice changes.

"Get up the nerve. I'll go inside first, and you follow me. If they ask anything, just say you are taking pictures of emergency housing."

Behind the creaky door, there is a tall wooden staircase leading into the dark. I wait for a minute – and then slowly and cautiously climb up the stairs, trying not to stumble. Mounting the last step, I breathe in a heavy odor of cheap tobacco and run an eye over a small room. A bright sun beam is streaming through a mud-spattered window, lighting up thick puffs of smoke and the somber faces of those who are crammed inside. The closest to me are two men sitting on tacky plinth stools – one with a face marked with deep wrinkles and scars from stab wounds and one with piercing blue eyes, a cross worn next to the skin and prison tattoos. A bit farther away, I see two stodgy-looking women and a frightened little girl in colorful striped tights. Everybody is looking at me and the camera hanging on my neck with suspicion and open hostility. But they clearly have a wholesome respect for Elena and hence put up with the loud shutter sound. Click, click, click. As soon as the man with tattoos signs a pile of papers, we come down the stairs, and a woman with a short haircut and a squarish chin follows us outside. Giving Elena a gimlet eye, she whispers something with her thin pale lips. I can hear only the last three words.

"Please help us."

Later, Elena will explain that there is only one family left in this building, which is totally dilapidated. They still cannot be resettled as nobody wants to have such neighbors: the two brothers we saw upstairs had spent years in prison after committing felonies. For some reason, the woman who lives in a neighboring apartment block – the one who saw us out – helps them and keeps begging the probation officer for help, too. In her eyes, Elena is the last hope.

Again and again, she greets passersby, coos with babies in buggies, nods at pedestrians – right until we stop by a long wooden house with broken windows covered with dust and dirt. Her voice changes.

"Get up the nerve. I'll go inside first, and you follow me. If they ask anything, just say you are taking pictures of emergency housing."

Behind the creaky door, there is a tall wooden staircase leading into the dark. I wait for a minute – and then slowly and cautiously climb up the stairs, trying not to stumble. Mounting the last step, I breathe in a heavy odor of cheap tobacco and run an eye over a small room. A bright sun beam is streaming through a mud-spattered window, lighting up thick puffs of smoke and the somber faces of those who are crammed inside. The closest to me are two men sitting on tacky plinth stools – one with a face marked with deep wrinkles and scars from stab wounds and one with piercing blue eyes, a cross worn next to the skin and prison tattoos. A bit farther away, I see two stodgy-looking women and a frightened little girl in colorful striped tights. Everybody is looking at me and the camera hanging on my neck with suspicion and open hostility. But they clearly have a wholesome respect for Elena and hence put up with the loud shutter sound. Click, click, click. As soon as the man with tattoos signs a pile of papers, we come down the stairs, and a woman with a short haircut and a squarish chin follows us outside. Giving Elena a gimlet eye, she whispers something with her thin pale lips. I can hear only the last three words.

"Please help us."

Later, Elena will explain that there is only one family left in this building, which is totally dilapidated. They still cannot be resettled as nobody wants to have such neighbors: the two brothers we saw upstairs had spent years in prison after committing felonies. For some reason, the woman who lives in a neighboring apartment block – the one who saw us out – helps them and keeps begging the probation officer for help, too. In her eyes, Elena is the last hope.

On the very next day, we meet at the police station entrance. I put the camera and the mobile phone into the locker (these are the rules) and follow Elena into the backyard. Among the cars demolished in recent accidents, there is a small alcove hidden in the corner – a favorite place of police officers and detained criminals for short smoke breaks.

A few drags and a small talk with colleagues about the day-to-day stuff and their bosses – this is how Elena's regular day at the police department begins. Having put the cigarette out, she heads off to do a house-to-house and inform her neighbors of new Internet frauds.

Along the way, we meet a twenty-something young man, walking lazily towards us.

"Look who it is! Long time no see!"

Elena stops and asks with a grin, "Well, haven't you caused any trouble yet? Better watch yourself!"

With these words and a short laugh, she lightly slaps him on the forehead with a pile of papers. He makes a wry face in turn. Having noticed my surprised look, Elena explains that this guy was one of the "difficult teenagers" she worked with at the child services. The teenager has grown up, but the difficulties remain the same.

Having walked one kilometer more, we enter the right building.

"Hi, I'm your local probation officer, Elena Peleschak. I'm here to warn you that under no circumstances should you provide your passport and bank details to strangers…"

Floor by floor, apartment by apartment. Stair flight by stair flight. Suddenly, a silver-haired old lady opens the door and invites Elena in. As we walk into a tiny kitchen, filled with a heavy smell of drugs, the old lady starts to wring her hands and wail that some stranger pounded on the door last night and threatened to murder her. Elena nods patiently.

"Don't worry, we'll figure it out."

Then she hands over her phone number written down with large figures on a folded piece of paper. Once we get out of the apartment, Elena sighs again and whispers that this lady appears to be out of her mind. According to Elena, there is a bunch of demented old citizens in Vytegra – no less than drunkards who rob local supermarkets on a daily basis.

We step outside, and I hear trills of laughter, coming from a nearby playground.

"Mom!"

A few drags and a small talk with colleagues about the day-to-day stuff and their bosses – this is how Elena's regular day at the police department begins. Having put the cigarette out, she heads off to do a house-to-house and inform her neighbors of new Internet frauds.

Along the way, we meet a twenty-something young man, walking lazily towards us.

"Look who it is! Long time no see!"

Elena stops and asks with a grin, "Well, haven't you caused any trouble yet? Better watch yourself!"

With these words and a short laugh, she lightly slaps him on the forehead with a pile of papers. He makes a wry face in turn. Having noticed my surprised look, Elena explains that this guy was one of the "difficult teenagers" she worked with at the child services. The teenager has grown up, but the difficulties remain the same.

Having walked one kilometer more, we enter the right building.

"Hi, I'm your local probation officer, Elena Peleschak. I'm here to warn you that under no circumstances should you provide your passport and bank details to strangers…"

Floor by floor, apartment by apartment. Stair flight by stair flight. Suddenly, a silver-haired old lady opens the door and invites Elena in. As we walk into a tiny kitchen, filled with a heavy smell of drugs, the old lady starts to wring her hands and wail that some stranger pounded on the door last night and threatened to murder her. Elena nods patiently.

"Don't worry, we'll figure it out."

Then she hands over her phone number written down with large figures on a folded piece of paper. Once we get out of the apartment, Elena sighs again and whispers that this lady appears to be out of her mind. According to Elena, there is a bunch of demented old citizens in Vytegra – no less than drunkards who rob local supermarkets on a daily basis.

We step outside, and I hear trills of laughter, coming from a nearby playground.

"Mom!"

Day 2. Tight Crimson Braids, Lunatic Old Lady and Heart-to-Heart Talk

A teenage girl with a long braid and curly baby hair runs to us. She hops up on Elena and squeezes her in a tight embrace. A minute later, the girl steps back and gives us a wide smile so that a dimple appears in each of her rosy cheeks.

"Sit down, monkey, I'll braid your hair."

The officer pulls out a hairbrush in one move, just like a magician pulls a rabbit out of a hat, and starts combing her daughter's hair – light brown, with a slight shade of crimson. Elena stops by the playground quite often to make sure her daughter Anya is safe and sound. The girl plays there alone, but her mom is in touch 24/7 – just one WhatsApp message away.

"I always tell her: if you see a drunk – run the other way and call me immediately. That's how it works."

I snap a picture, and Anya laughs.

The sun starts to go down, flooding old five-story apartment blocks with warm orange light, and we head off to the police department. At some point, Elena slows down. It turns out her mom lives in one of these gray houses. Elena takes care of her almost every day: her mom was fighting cancer for several years, and fortunately, it has gone away. Now, she is in remission.

"And what about your dad?"

"He is no more," Elena sighs heavily. "By the way, I take after him a lot. My mom is a softie, but dad... Before I was born, he hadn't missed a single fight. But he always took the side of those who were right – I haven't heard a single bad word about him. He died when I was nine. You know, an ulcer and doctors' negligence. Now, I wouldn't let it happen – with my attitude, I would get the entire hospital on red alert. The head doctor would be present at the operating table."

She sighs again – I feel that she misses her dad very much. And I do believe that she actually takes after him.

"Sit down, monkey, I'll braid your hair."

The officer pulls out a hairbrush in one move, just like a magician pulls a rabbit out of a hat, and starts combing her daughter's hair – light brown, with a slight shade of crimson. Elena stops by the playground quite often to make sure her daughter Anya is safe and sound. The girl plays there alone, but her mom is in touch 24/7 – just one WhatsApp message away.

"I always tell her: if you see a drunk – run the other way and call me immediately. That's how it works."

I snap a picture, and Anya laughs.

The sun starts to go down, flooding old five-story apartment blocks with warm orange light, and we head off to the police department. At some point, Elena slows down. It turns out her mom lives in one of these gray houses. Elena takes care of her almost every day: her mom was fighting cancer for several years, and fortunately, it has gone away. Now, she is in remission.

"And what about your dad?"

"He is no more," Elena sighs heavily. "By the way, I take after him a lot. My mom is a softie, but dad... Before I was born, he hadn't missed a single fight. But he always took the side of those who were right – I haven't heard a single bad word about him. He died when I was nine. You know, an ulcer and doctors' negligence. Now, I wouldn't let it happen – with my attitude, I would get the entire hospital on red alert. The head doctor would be present at the operating table."

She sighs again – I feel that she misses her dad very much. And I do believe that she actually takes after him.

On the third day, I come to Elena's place in the morning. When I find the right entrance in the panel-built house, I barely hold back a smile: there is a notice with a little black-and-white picture of the red-headed police officer and her phone number. The funny thing is that I saw her hanging such notices, sticking them to the walls with nothing else but a band-aid.

I climb the concrete stairs up to the fifth floor, ring the doorbell, and a sharp long trill breaks the silence. Elena opens up the door, dressed in a cozy gray shirt and black leggings.

"Come on in!"

Now, when she is not wearing her police uniform, I can spot numerous tattoos. There is a big letter "A" with little flourishes on her chest. "A" stands for Anya – this one honors her daughter. Down the right leg, a dark-blue heart is "burning" up in flames. Later, Elena will tell me that the heart tattoo is a matching one. Her childhood girlfriend, who died a few years ago, had the exact same one.

A short step forward is followed by a flip of the key in the keyhole. Elena turns around, and I notice a huge Metallica logo on her shoulder blade. I have already seen such a logo on the screensaver at her office.

From the doorway, I can detect a familiar smell of mint cigarettes, although now it is accompanied by the smell of cats and instant coffee. There are two smokers in the apartment: Elena herself and her husband. As for the cats, there are three of them, with each having been saved from hunger, cold or the threat of being put down. One cat has recently delivered kittens, so there is a cardboard box hidden in the living room, which serves as their little shelter.

I climb the concrete stairs up to the fifth floor, ring the doorbell, and a sharp long trill breaks the silence. Elena opens up the door, dressed in a cozy gray shirt and black leggings.

"Come on in!"

Now, when she is not wearing her police uniform, I can spot numerous tattoos. There is a big letter "A" with little flourishes on her chest. "A" stands for Anya – this one honors her daughter. Down the right leg, a dark-blue heart is "burning" up in flames. Later, Elena will tell me that the heart tattoo is a matching one. Her childhood girlfriend, who died a few years ago, had the exact same one.

A short step forward is followed by a flip of the key in the keyhole. Elena turns around, and I notice a huge Metallica logo on her shoulder blade. I have already seen such a logo on the screensaver at her office.

From the doorway, I can detect a familiar smell of mint cigarettes, although now it is accompanied by the smell of cats and instant coffee. There are two smokers in the apartment: Elena herself and her husband. As for the cats, there are three of them, with each having been saved from hunger, cold or the threat of being put down. One cat has recently delivered kittens, so there is a cardboard box hidden in the living room, which serves as their little shelter.

Day 3. "A for Anya," Metallica and Cardboard Medal

The only room where there is no smell of cigarettes at all is the kid's room. Instead, it smells like hay and sawdust. That is because Anya lives with an orphaned rabbit, whose first owner died of thrombosis. Elena arrived on a call and could do nothing but take the fluffy pet home.

Clack, clack, clack. Anya runs out of her room and starts strutting out in front of the camera, showing off the heels her mom bought her for this year's first day of school.

"Hun, we had an agreement! You must read at least one chapter."

Elena sends Anya to her room to read Mowgli. It is August, so Elena has a chance to control her daughter's summer reading at least in the mornings when she has not gone to work yet. However, during the school year, things are different: she helps Anya with her homework via phone and makes her send pictures of the completed assignments on WhatsApp. Actually, Elena takes Anya's upbringing very seriously and does her best to be a good mom and a role model for her daughter. She never smokes in front of Anya herself. Also, there is a ban on alcohol when Anya is home – it is simply a no-no.

Having dealt with Anya's reading, Elena offers me milk semolina porridge with butter and with no lumps, and I gladly sit down by the window. My gaze falls upon a shabby wall by the kitchen table, and Elena hurries to explain that it is official housing and they are hardly the first residents here. They have not got round to replacing the wallpaper yet, even though they have already bought several rolls – light pink, with mother-of-pearl and sparkles. But there is one good thing about the walls that no one is afraid to blemish: they can be used as a canvas.

Clack, clack, clack. Anya runs out of her room and starts strutting out in front of the camera, showing off the heels her mom bought her for this year's first day of school.

"Hun, we had an agreement! You must read at least one chapter."

Elena sends Anya to her room to read Mowgli. It is August, so Elena has a chance to control her daughter's summer reading at least in the mornings when she has not gone to work yet. However, during the school year, things are different: she helps Anya with her homework via phone and makes her send pictures of the completed assignments on WhatsApp. Actually, Elena takes Anya's upbringing very seriously and does her best to be a good mom and a role model for her daughter. She never smokes in front of Anya herself. Also, there is a ban on alcohol when Anya is home – it is simply a no-no.

Having dealt with Anya's reading, Elena offers me milk semolina porridge with butter and with no lumps, and I gladly sit down by the window. My gaze falls upon a shabby wall by the kitchen table, and Elena hurries to explain that it is official housing and they are hardly the first residents here. They have not got round to replacing the wallpaper yet, even though they have already bought several rolls – light pink, with mother-of-pearl and sparkles. But there is one good thing about the walls that no one is afraid to blemish: they can be used as a canvas.

I look around the room and notice spidery writing near the doorway. The text reads:

"06.08.21 A.D. at 4:00 pm Elena Aleksandrovna cooked dinner without consulting with me!!! An HONORABLE MENTION for decisive actions must be granted!"

"08.08.2021 at 7:35 pm Aleksey Ivanovich said my soup was "yummy" rather than "okay!!!" That's a success as he expanded his vocabulary and learned new words!!!"

These are the notes Elena and her husband leave for each other. Aleksey works at the MRF, and because of their tight schedules, they see each other rarely. Today is a perfect example – Aleksey, a tall man with kind brown eyes, comes home to have lunch, but he's barely had time to get his coat off when his phone starts ringing in his pocket. This is an emergency call. He gives his wife a brief goodbye kiss and leaves straight away.

"Sometimes, he sets out to work while I'm sleeping. Then, when I come back at 3:00 am in the morning, he's the one who's asleep. "Well", I think. 'Maybe we'll be lucky to see each other next week,'" Elena laughs, shrugging her shoulders.

I give a knowing toss of the head. Aleksey is Elena's second husband; to be more exact, a common-law one. She divorced Anya's dad as they had different goals in life, but they still remain friends. Anya spends every Sunday at his place, and Elena walks their dog from time to time – that is why they often joke, calling each other "Sunday dad" and "Sunday mom." At 32, Elena does not want to walk down the aisle ever again. She pawned her wedding ring and bought gold earrings for her daughter instead – Anya is thrilled and almost never takes them off.

"06.08.21 A.D. at 4:00 pm Elena Aleksandrovna cooked dinner without consulting with me!!! An HONORABLE MENTION for decisive actions must be granted!"

"08.08.2021 at 7:35 pm Aleksey Ivanovich said my soup was "yummy" rather than "okay!!!" That's a success as he expanded his vocabulary and learned new words!!!"

These are the notes Elena and her husband leave for each other. Aleksey works at the MRF, and because of their tight schedules, they see each other rarely. Today is a perfect example – Aleksey, a tall man with kind brown eyes, comes home to have lunch, but he's barely had time to get his coat off when his phone starts ringing in his pocket. This is an emergency call. He gives his wife a brief goodbye kiss and leaves straight away.

"Sometimes, he sets out to work while I'm sleeping. Then, when I come back at 3:00 am in the morning, he's the one who's asleep. "Well", I think. 'Maybe we'll be lucky to see each other next week,'" Elena laughs, shrugging her shoulders.

I give a knowing toss of the head. Aleksey is Elena's second husband; to be more exact, a common-law one. She divorced Anya's dad as they had different goals in life, but they still remain friends. Anya spends every Sunday at his place, and Elena walks their dog from time to time – that is why they often joke, calling each other "Sunday dad" and "Sunday mom." At 32, Elena does not want to walk down the aisle ever again. She pawned her wedding ring and bought gold earrings for her daughter instead – Anya is thrilled and almost never takes them off.

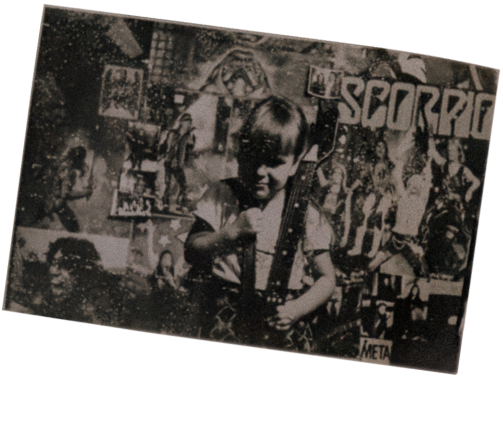

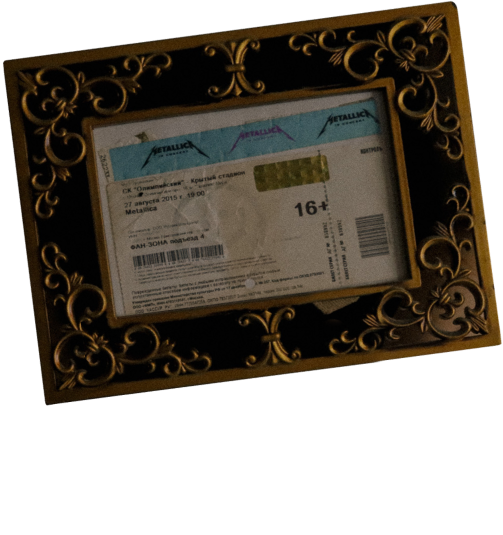

Meanwhile, I look at the walls in the living room, adorned with pictures. Suddenly, Elena opens a wooden wardrobe with a mysterious smile and pulls out a photo frame. But instead of a picture inside, there is a ticket to the fan zone of the Metallica concert from 2015. After that, she grabs a photo album from the shelf and shows a picture where she, still a little girl, holds an electric guitar in her arms in front of posters of The Scorpions. She inherited the love for rock from her elder brother, who now lives in Saint Petersburg and organizes punk festivals.

"Have you ever thought of moving?" I ask.

"I don't want to live in a big city," Elena answers with unshakable confidence and adds, "But in a village, I would feel like howling, too. I need society after all. Vytegra is just perfect for me. I walk asphalted roads, but it's not much different from the countryside."

Next to the photo frame, I notice a cardboard medal. My first thought is that it must be from her daughter, but I turn out to be wrong: the red and yellow circle with curvy edges was cut out by her husband – for "heroic potato peeling."

Once the hands of the clock make a straight line, notifying us that it is already half-past one, Elena starts to hastily get ready.

"Dear, all the cars are busy. The driver will arrive only in fifteen minutes. Will you wait?" a taxi dispatch asks in a high-pitched voice. Elena is going to spend the rest of the day at her office: she has to file reports, update the database, and sort out tons of important papers.

"Have you ever thought of moving?" I ask.

"I don't want to live in a big city," Elena answers with unshakable confidence and adds, "But in a village, I would feel like howling, too. I need society after all. Vytegra is just perfect for me. I walk asphalted roads, but it's not much different from the countryside."

Next to the photo frame, I notice a cardboard medal. My first thought is that it must be from her daughter, but I turn out to be wrong: the red and yellow circle with curvy edges was cut out by her husband – for "heroic potato peeling."

Once the hands of the clock make a straight line, notifying us that it is already half-past one, Elena starts to hastily get ready.

"Dear, all the cars are busy. The driver will arrive only in fifteen minutes. Will you wait?" a taxi dispatch asks in a high-pitched voice. Elena is going to spend the rest of the day at her office: she has to file reports, update the database, and sort out tons of important papers.

"I need to take your family portrait by the submarine. My professor told me not to come back without a posed picture like that," I rattle off the second I come in.

Then I take a closer look at Elena – I see that something has changed. Her hair went from just red to flaming red and now is shining in the sun even brighter. I am not surprised though: I know that she often carries out experiments with her hair. She once told me how her daughter and she both dyed their hair pink during the school break. Anya still has pinkish wisps framing her face.

"I'll call Lesha," Elena says. Lesha is short for Alexey. "He was planning to go fishing, but maybe he'll be able to put it off a bit."

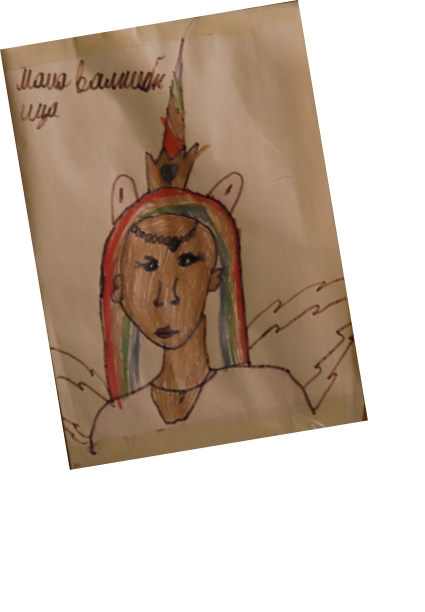

I note that now she has even more similarities with the portrait her daughter drew – the one that is hanging on the wall at her office. In the picture, she has colorful hair, and the sweet caption above her head reads: "Mom is a fairy."

The day is going to be rather ordinary: we will have to go through our daily routine, responding to regular calls – another elderly lady has had a nightmare, an old gentleman has been tricked by some phoneys, and some neighbors are having a fight. We walk from one house to another. Faces, houses, apartments, and testimonies replace each other like kaleidoscopic images. However, there is one call Elena decides to handle on her own, and she refuses to take me with her.

She says firmly, "We'll be in touch. Go have lunch now."

Two hours later, the officer comes back looking visibly tired. She seems a bit haggard, and her voice sounds quieter than usual. With a heavy sigh, she says that some lunatic had a flare-up: he locked himself in a room and was trashing everything inside, so she had to get him out. Just like in a movie: with a siren, straitjacket and a bunch of nurses.

Then I take a closer look at Elena – I see that something has changed. Her hair went from just red to flaming red and now is shining in the sun even brighter. I am not surprised though: I know that she often carries out experiments with her hair. She once told me how her daughter and she both dyed their hair pink during the school break. Anya still has pinkish wisps framing her face.

"I'll call Lesha," Elena says. Lesha is short for Alexey. "He was planning to go fishing, but maybe he'll be able to put it off a bit."

I note that now she has even more similarities with the portrait her daughter drew – the one that is hanging on the wall at her office. In the picture, she has colorful hair, and the sweet caption above her head reads: "Mom is a fairy."

The day is going to be rather ordinary: we will have to go through our daily routine, responding to regular calls – another elderly lady has had a nightmare, an old gentleman has been tricked by some phoneys, and some neighbors are having a fight. We walk from one house to another. Faces, houses, apartments, and testimonies replace each other like kaleidoscopic images. However, there is one call Elena decides to handle on her own, and she refuses to take me with her.

She says firmly, "We'll be in touch. Go have lunch now."

Two hours later, the officer comes back looking visibly tired. She seems a bit haggard, and her voice sounds quieter than usual. With a heavy sigh, she says that some lunatic had a flare-up: he locked himself in a room and was trashing everything inside, so she had to get him out. Just like in a movie: with a siren, straitjacket and a bunch of nurses.

Day 4. Non-Yellow Submarine, Nurses and Goodbyes

Soon, Aleksey arrives, we pick up Anya and go to take pictures by the submarine altogether. We leave an old car at the parking lot and walk down the alley surrounded by tall soughing birches. The air is filled with the grassy fragrance of river water. Elena and Aleksey walk arm-in-arm and talk about something quietly. Anya runs about the lawn, squealing and picking up clover flowers to make a bunch for her mom. Ironically, sometimes it takes a photography student from Saint Petersburg to gather the family together for at least half an hour.

Right after the photo shoot, we take Anya to her grandma and then head to a local diner next to the police department.

"I want meat," Elena declares loudly. "I am bloodthirsty today."

The diner is filled with such an odor of fried cutlets that even I cannot refuse to order some. We have dinner in silence: all one can hear is a camera clicking from time to time and forks scratching thin glass plates.

Although with a delay, Aleksey sets out to go fishing, and I have a bus to Saint Petersburg the very next morning. I have spent a week in Vytegra, but it feels like a month, not less. The red-headed officer gives me a goodbye hug and, zipping the dark-blue uniform up to her chin, disappears behind a steel door of the local police department. As I watch her go, I blink in the sunset rays, which remind me of her flaming wisps.

I do not know if I will ever come back to this town, but what I do know is that I am going to miss Elena and her loud laughs, ginger hair and expressive sighs – a rare display of weakness that even such a strong woman as her can sometimes show.

Right after the photo shoot, we take Anya to her grandma and then head to a local diner next to the police department.

"I want meat," Elena declares loudly. "I am bloodthirsty today."

The diner is filled with such an odor of fried cutlets that even I cannot refuse to order some. We have dinner in silence: all one can hear is a camera clicking from time to time and forks scratching thin glass plates.

Although with a delay, Aleksey sets out to go fishing, and I have a bus to Saint Petersburg the very next morning. I have spent a week in Vytegra, but it feels like a month, not less. The red-headed officer gives me a goodbye hug and, zipping the dark-blue uniform up to her chin, disappears behind a steel door of the local police department. As I watch her go, I blink in the sunset rays, which remind me of her flaming wisps.

I do not know if I will ever come back to this town, but what I do know is that I am going to miss Elena and her loud laughs, ginger hair and expressive sighs – a rare display of weakness that even such a strong woman as her can sometimes show.